Machines outperform humans at a million small tasks, but they lack any understanding of how those tasks fit together. That fractured competence can pose a big problem for the design of large data processing pipelines.

To get a computer to do anything well, you have to break your task into pieces and then refine each piece until you’re in danger of overcommitting yourself to some set of assumptions.

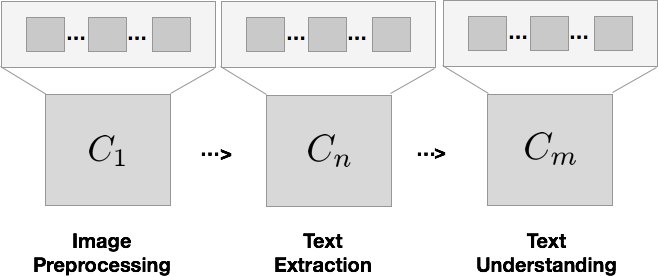

Consider how you might sketch a data pipeline that processes photos of legal documents:

Big picture diagram of a pipeline for document understanding. Assumptions you

commit to in the early stages of the pipeline stay with you forever… impacting

how well you do at the end of the pipeline.

Big picture diagram of a pipeline for document understanding. Assumptions you

commit to in the early stages of the pipeline stay with you forever… impacting

how well you do at the end of the pipeline.

Component 1 might remove noise and background, Component 2 converts the image into text, and Component 3 tries to understand the text. Each of these components itself further decomposes into hundreds of small engineering decisions.

If I asked you to build this pipeline, it would seem reasonable to approach your construction literally: building one image processing stage, and one text extraction stage, and one text understanding stage. Your system would end up looking just like the diagram.

But consider how dangerously the assumptions you commit to interact if you do that. Each small assumption made in Component 1 carries forward in its output to Component 2, and then Component 3, forever limiting the upper bound on performance downstream.

Conjunction dysfunction

At heart, the problem is that yield at each Step N is dependent upon the yield at Step N-1 (and therefore transitively upon all steps before it). It’s a data version of the “pipeline problem” universities face with respect to underrepresented groups in certain fields of education.

In a serial pipeline, outcomes in early steps compound their influence over all steps that come after. You end up with what you might call conjunction dysfunction: a situation where the performance of your system as a whole depends upon every component getting everything right.

So if you implement your data pipeline just like the diagram above, its performance is going to be heavily impacted by how long it is. The probability that some piece of input is correctly processed is (avg_yield) ^ (num_components):

LaTeX’s seldom-used \sad_equals operator. The cold hard math of solving for the 80% case at each stage of a long data processing pipeline. At 80% average yield, it only takes the conjunction of 7 components to dip below 20% overall performance!

Faced with this, one strategy is to say:

- “Well, I’ll plan on doing my best when implementing each component!”

This is equivalent to improving avg_yield. But as the length of your pipeline adds up, you just can’t run away from harsh reality of multiplying probabilities. Let’s assume your pipeline has this conjunctive property and each component on the pipeline performs with 80% accuracy. It only takes a conjunction of 7 components to render your pipeline’s accuracy only 20%!

So instead you might say:

- *“Fine, I’ll limit the length of my pipeline. Simplify things.”*This is equivalent to decreasing the exponent, num_components. But simplification is often either too hard or too time intensive. It requires you to outsmart the problem you’re dealing with. And the whole reason we’re in this mess is because we’re trying to solve a hard problem.

So here’s a different approach…

Increasing average yield with Ensembles of “Good Enough”

Here’s an alternative to spending your time creating the One Big Perfect Model:

Create multiple small models. Take a different approach with each. Aim for being “good enough”.

It’s often orders of magnitude easier to score a B than an A. So relax, man! Aim to be a B student…. but **do it over and over again, with a different route each time. **Then, create a **Picker **function that looks at the results of all these “Good Enough” models and selects the right result.

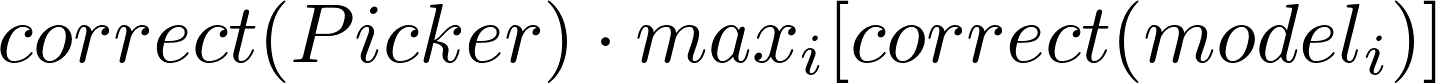

If you assume the Picker merely selects the right model (rather than merges their output), the performance of an Ensemble of Good Enough becomes:

The probability your Ensemble of “Good Enough” is correct is the probability

that one of your Good Enough Models is correct times the probability that your

picker selects the right answer.

The probability your Ensemble of “Good Enough” is correct is the probability

that one of your Good Enough Models is correct times the probability that your

picker selects the right answer.

You can actually argue that the ensemble performance is better than this because you implemented each model with a different strategy. They won’t all fail in the same way, meaning they’ll correctly perform on different subsets of your data. So if your Picker works well enough, the performance of the ensemble is more than the performance of its best performing component.

So here’s my hand-wavy claim about data pipelines: the moment some component becomes “Good Enough”, your time might be better spent switching to the happy math of an ensemble of Good Enough rather than optimizing every last piece into the headwinds of conjunction disfunction.

Real world example: detecting and decoding QR codes

Here’s a real world example of this approach from last week.

Our team at Instabase needed to validate an enormous collection of documents stamped with QR codes, but the image quality of these documents was extremely variable.

Scouring the literature, it became apparent that there are quite a few strategies for locating a QR code in 3D space so you can transform it into a proper square image to pass to a QR decoding module. But we ran into a problem: given the variance in image quality we had, some of these approaches weren’t as universal as they claimed to be.

Should we expand upon them? Add more heuristic tricks? Maybe more image cleanup in the pre-processing step?

Enter the Ensemble of Good Enough. Here are just a few of the Good Enough approaches we pursued:

Three strategies for locating the position of a QR code in an image (which may be warped or skewed or otherwise distorted). Importantly, all three methods may yield many guesses. Sometimes hundreds.

The beautiful thing about QR codes is that you know when you are correct because the decoder fails to work if you aren’t.

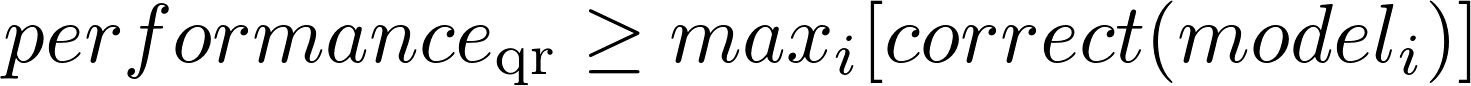

That means a QR ensemble’s Picker function is perfect. If any model is correct, it will pick it, rendering the performance of the ensemble a beautiful:

Using that model of performance as our guiding metric, we were able to have a fun time pursuing a variety of approaches rather than fighting the diminishing returns of trying to make a single approach work across the board. A win for performance and morale.

Takeaway: Approach life probabilistically

These kinds of things are always situation dependent. The fact that a QR ensemble’s Picker function is perfect makes this a bit of an unfair anecdote in favor of this approach.

But I think there is a general takeaway that extends beyond even ensembles to programming in general:

- Serial pipelines become brittle with length, as errors cascade from earlier steps down to later ones.

- Most of the code we write, when you think about it, is really a long serial pipeline. The state at each step depends upon the state emitted by the prior step.

- Any time you find yourself fighting complexity. Ask yourself if your standards are too high. Instead of doing perfectly one time, why not aim for Good Enough multiples times? Roll the dice a bit. Then you’ve just got to figure out a way to merge the results.

Come think about these things at Instabase.

If this is the kind of thinking you like to wrestle with, reach out and say hello. We’re building an amazing team at Instabase and looking to grow in everything from systems to machine learning to web development.