(And how to use it to start one)

Here’s the problem: **there’s a chicken-and-egg problem with protesting. Many people want to JOIN a march, but few people want to START a march. **This blog post shows how a bit of simple math, combined with a mobile app, could overcome that.

This blog post is (quite literally) a back-of-napkin sketch, and I’m sure the ideas are well trodden ground. I’m not claiming any novelty — just some after-dinner food for thought.

Modeling a Protest

Any group can be divided into two kinds of people at a snapshot in time. Those who are protesting and those who aren’t.

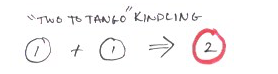

A person is either protesting or not protesting

A person is either protesting or not protesting

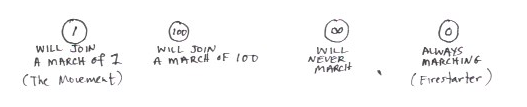

Of course that’s not the whole story. Many people who aren’t protesting would, if only the group got big enough for them to feel comfortable participating. We can call this activation impedance.

If your activation impedance is 1, it means you’ll start protesting if you see just one other person doing it (you rebel). If it’s 100, it means you’ll only join groups of 100 or more. If it’s ∞, it means you will never protest. If it’s 0, it means you are comfortable bringing the party all by yourself.

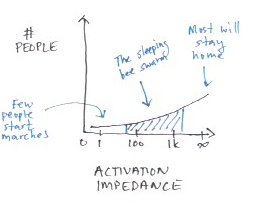

We know that there are very few people with low activation impedance (willing to start a protest). And for most it’s very high. So the critical question of kindling a march in the streets is *can you find & connect enough people with low impedance to activate that middle segment that would otherwise lay dormant? *Then you have real numbers hit the streets.

A lot of us identify with that middle segment. We sit or stand at work, caring a lot about what’s going on in the world, but too busy/tired/complacent to proactively organize. What comes below shows how to overcome that problem.

The Math of Joining a Protest

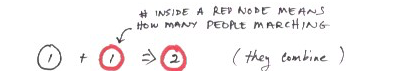

Well, this is basically a simple math problem with our invented protestor symbols. An unactivated person with impedance 1 plus a protest of size 1 equals a protest of size 2.

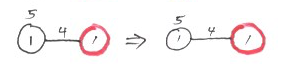

Just like before, the number inside a black circle denotes the impedance of that person. But the number inside red circle will denote the size of the protest.

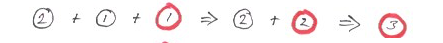

There’s also the scenario where two otherwise unactivated people could agree to protest together, so long as the result exceeds each of their individual activation impedances. (The “I’ll do it if you do it” scenario)

We can similarly reason about protests that will fail to attract a new member. In the case below, the onlooker is only comfortable joining a protest of size 2 and above, so does not join the protest of size 1.

But here’s where things get interesting. The real world has millions of such nodes, and these **activations **can cascade, like this:

In this case, the group of three people starts with one protesting. That’s enough to activate the second, and then the protest of two is enough to activate the third.

Factoring in Location

We know that starting a protest isn’t just about willingness, it’s about location. I will be in San Francisco on January 20th, and the flight to D.C. exceeds my tolerance to travel to protest. But that’s not true of everyone.

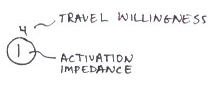

First, let’s add a new number to each node: the **willingness to travel. **The person below has an activation impedance of 1 and a willingness to travel 4 units of distance.

We can represent distance by forming all the nodes into a fully connected graph. The edge weights are the distances between people.

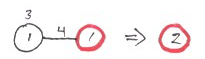

And with that, we have the same old math rules, but we have two separate conditions we have to satisfy for activation. So in some cases activation will happen:

But in other cases activation won’t. Not because the impedance was too high, but because the distance was too far.

These Graphs are all you need to model whole cities

They look simple when you just draw a few circles and lines, but that’s because the mechanics of snowballing really do seem pretty simple.

The only difference between a city of millions and the figures above is how many circles you draw (more realistically: how many the computer models). For any city of N people, you’d need N circles (each with an impedance) and N² lines to encode the distances between them all.

Answering the question “Could a Protest of Size N Occur?”

The million dollar question is whether a protest of any significance could occur at some place and time. Activists want to start them, and governments want to be prepared to maintain safety.

First you have to pick the size you’re interested in, but note that just means selecting the number inside of a red circle.

Next we draw the graph of all nodes of the population we’re interested in (a city, a state, a country..). That graph begins with all nodes unactivated. we’ll call it “Graph 0”

The question of “Could a protest of Size N Occur?” is then equal to the question of whether a sequence of arithmetic operations on “Graph 0” could be performed such that it will eventually produce a graph containing an activated node of Size N. The graph above, for example, is capable of resulting in a protest of size 3 in two operations.

The bigger the graph, the more the computer has to spin its wheels to generate an answer for you, but the important thing is that (1) it can do it, and (2) once it does, it’s also produced a roadmap for getting the protest going: Alice and Bob start, then they march over to Charlie. At this point Deborah and Eve will join, triggering… and so on, and so on.

How to Start a Protest

So back to the starting question of how to start a protest. The old fashioned way, of course. But technology can probably be a useful tool.

If a challenge of protest organizers is how to get the activation energy to really unlock the masses, then a useful tool could be an app that lets people register their location, activation impedance (how big a protest it has to be before they’d be willing to join), and their travel willingness.

Protest organizers could then play out scenarios: if I could gather 15 people on Market Street, would that be enough to create a protest of size 10,000 — providing everyone made good on the promise they punched in their phone?

The simple modeling above says the app would be able to give you a pretty easy yes/no answer to that question. And help you out along the way by sending notifications that a protest nearby you has just reached a size that you’re comfortable participating in.

I Sit in My Office and Have the Feels

Like many of you, I’m sure, I’ve spent several afternoons this election cycle struggling to focus at work while I really want to take to the streets. Instead, I open twitter and seek catharsis by reading tweets from other angry people.

Perhaps with a bit of technical assistance, we could facilitate the conditions that would activate all those office workers staring despondently out the window. And achieve something with more social impact than browsing Twitter.

EDIT: Responses to Questions I’ve Gotten:

This doesn’t take into account why people are protesting, and surely that’s important. 100% agree. But, insofar as modeling how a protest forms so that software could assist its creation, agreement about purpose, for the most part, is a simple “yes/no” filter that can be applied.

Why does your URL have the word “riot” in it? I just want to state clearly I don’t support violence or destruction of property. I was trying to create an eye-catching title, and Medium immortalized the first draft of it in the URL.

There is some academic work in this area already. Feel free to ping me if you’d like links to the studies folks have sent.

People aren’t accurate self-reporters of their own impedance & travel willingness, and this would damage the ability of the model to be effective. Yeah, that’s a good point. The follow-up meta-question, I suppose, would be whether the noise within the self-reported values compounds to enough to prevent the overall physics of the model from working.