I’ve been doing a lot of image processing lately, with the goal of extracting the structured data visible inside an image. While I’ve still got beginner-brain and a mountain of OpenCV tutorials fresh in my mind, I thought I’d write a bit about how to successfully approach image extraction problems.

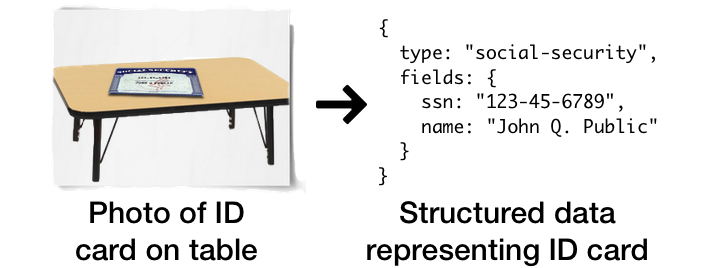

Here’s one scenario I’m working with: many online services ask users to prove their identity with photos of ID cards, paystubs, bank statements, and the like. Rather than running a standard OCR on these images, it would be nice to directly recover the structured data they represent.

This post records the first two “ah hah!” moment’s I had while diving into that problem. Both are about how to organize your thinking, rather than any specific OpenCV trick:

- How to decompose an image extraction problem into smaller problems

- How to decompose an image extraction problem into “side” problems

How to decompose an image extraction problem into smaller problems

When I first started, this kind of task felt insurmountably large because I had no idea how to make incremental progress. Here’s the recipe I’ve found for breaking down a large image task into smaller pieces:

Force yourself to write down the sentence

“I’ve got X… but if only I had Y, I could easily produce Z”

The transformation Y→Z should be something so simple that you already see clearly how to do it. In fact, your next step should be to implement and test it right away. Having solved the easy problem Y→Z, you’ve now simplified the hard problem into only X→Y.

Here are my initial X, Y, and **Z **for the social security card example:

- **I’ve got **a random photo containing an SSN card…

- **but if only I had **a rectified, registered [] *social security card image…

- I could easily use the fixed geometry of the card to simply crop and OCR exactly the the SSN and Name fields.

[] Note: Rectified means ‘projected onto a reference plane’ and [2] registered means ‘aligned to a known coordinate system.’*

Having solved Y→Z, now I’m left with only the problem “how do I take my input image **X **and produce a rectified, registered image Y?”

- If I know how to solve that directly, great!

- If I don’t, I can just repeat this decomposition over again, dividing the problem **X→Y **into some new problem X→X2→Y.

Read on for a variant of this decomposition that will help us do exactly that second part.

How to decompose an image extraction problem into “side” problems

This is a point that feels obvious in retrospect, but it took me a while to realize it:

Sometimes Y is just extra information. It’s not an intermediate version of your image.

When I first started, I had this idea that image processing was like 35mm film processing: you take a photo and apply various baths and chemicals, refining it until you see the picture you want. Except in our case, the baths and chemicals are kernels and matrix operations.

This mental model is all wrong.

The successful model is to remember that you can go on *side adventures with copies of the image. *These side adventures might destroy the data in the image, but they will produce valuable data that you can then use when returning to your original image.

In other words:

- Clone(X)→YGo on a side adventure with a clone of X to compute statistics Y

- (X, Y)→Z

Use the combination of **X **and Y to compute Z

Let’s see how that looks in our social security cards. Remember, our job is to isolate, rectify, and register the social security card.

Here’s one simple approach: we might grey the image, blur it, edge-detect it, contour detect it, and then retain only the contour that represents the largest 4-gon.

Sketch of the side mission to find some data Y that will be useful in taking X→Z.

We now throw away all the data on that side adventure and just keep the coordinates of the 4-gon, which we’ll call Y.

Returning back to the original image, we can use that polygon to extract the region of the image that we think is our card, and then apply an off-the-shelf transform to rectify it. (X, Y)→Z.

If we have the (correct) coordinates of the 4-gon that represents the card, we can easily extract that region of the image and rectify it to produce the shape.

Rinse, repeat, you’re done!

I’ve obviously skipped some steps above: I’m not registering the rectified social security card against a known template, so the coordinates may be a bit off (in real life, the rectified card won’t be as perfectly isolated as the diagram above).

But that’s OK, because to add any extra steps, you can just keep applying the two problem decomposition patterns above.

And when you’re ready to ship code, these patterns provide natural groupings that you can use to divide code into modules that will make sense to a future reader. I don’t know about you, but long, linear OpenCV functions look like gibberish to me. Much easier if you can help someone visualize what you were thinking when you did what you did:

Toward extraction with deep nets

This whole writeup is based on experiences with what you might call “old school” image processing, in which the human comes up with an entirely heuristic model to achieve their objective.

I’m curious to find out how it holds up as a way to approach image extraction problems using deep learning, which tends to favor a more data-heavy / heuristics-light approach.

If you have opinions.. let me know!

Note: we’re hiring!

If you like solving puzzles like this and want to make a big impact in industry, reach out and say hello. We’re building an amazing team at Instabase and looking to grow.